|

I had read that Tehuantepec storms were difficult, even impossible to anticipate; not true. The U.S. Navy’s weather prediction center, known by the unpronounceable acronym FNMOC, clearly showed that a gale would be a’brewin’ in the Gulf of Tehuantepec days before the event. It was plain to see in the wave height and direction section of its website, which I had consulted before leaving Barillas. It was plain to see-a patch of 10-foot seas coming off the Mexican coast. FNMOC’s computer-modeled forecasts had served me well for years, though most mariners seem unaware of this free public resource.

Tehuantepec storms originate in the Gulf of Mexico and occur when a high-pressure system follows a low across Texas and into the Caribbean. This high brings north winds, and these funnel through a break in the mountains that run down Mexico like the spine of a stegasaurus. That wind accelerates in a venturi effect, then roars out the other side with gale force, creating square 10-foot seas hundreds of miles into the Pacific.

Eric Kunz, Furuno’s product develop manager, had warned me about “Tehuantepeckers,” when I explained Ho’Okele’s route to him. So had our naval architect, Lou Codega, who had once witnessed Tehuantepecker bedlam from the deck of a ship. It was Kunz who gave me the classic advice about “keeping one foot on the beach.”

After our successful passage through a Costa Rican Papagallo storm the week before, I decided we would just bull through the Gulf of Tehuantepec. A boat could put down roots waiting for a weather window; January sees Tehuantepeckers 19 out of its 31 days.

Twenty-four hours-that’s all Chef Charles and I would have to endure. We had once gone offshore for 3½ days straight in the open cockpit of a 30-foot sailboat in winter conditions, two-hours on, two hours off for 84 hours. Our attitude was: Get it over with. I headed Ho’Okele toward the beach.

We had left Marina Barillas in El Salvador two days before on a 475-mile run to a little resort town in the Oaxaca region called Santa Cruz. Our conversation with the Mexican Navy occurred about 8:30 a.m. on Jan. 3. By 2 p.m. with our destination still 30 hours away, Ho’Okele was in the thick of it.

Winds were averaging about 35 knots, but, as predicted, seas were only 1 to 2 feet a half mile off the beach. That didn’t stop the wind from clawing at these waves and hurling bits of them through the air; being inside the deckhouse was like driving through a carwash-at least to starboard.

The four remaining hours of daylight gave me the chance to work out a system for keeping a consistent half-mile out once the sun went out. It would have been great if the shore ran true because the autopilot was unaffected by the force of the winds, but the shoreline ran from southeast to northwest, becoming incrementally more westerly as we got into the gulf.

Obviously the radar was a terrific tool for maintaining our interval, so I would get the boat on course using the radar than put a cursor waypoint on the plotter so the autopilot would have something to steer to. Then it would be just a matter of monitoring our progress and adjusting our course with new cursor waypoints as the shore curved.

All this sounds pretty straightforward, and in daylight, it was. Night would be different-no moon, nothing to see but brine and blackness. We might as well have been a submarine. So besides keeping a foot on the beach, Ho’Okele’s radar would be our only way to avoid collision with other stray vessels or big debris-a process of regularly varying range and gain.

The one problem that surfaced with our Tehuantepec videogame was the C-Map chart. It was wrong. While we were motoring a half mile out, the chart showed Ho’Okele plowing sand a half-mile inland. Fine, I thought, as long as the error is consistent, but that was tired thinking; because we were incrementally changing course, the error could not stay constant relative to the boat’s heading.

It was a lapse that almost bit us in the butt, and I think it happened around midnight.

I was looking down into the chartplotter and saw a number changing-7, 6, 5, 4, 3. Whoa! That’s the depthsounder readout! I took control of the boat and turned us 90 degrees to port to head offshore. The depth rose almost immediately to 5 feet but took what seemed like forever to get over 10.

We had almost run into sand berm alongside the mouth of a big lagoon. The chart showed this obstacle more than a mile ahead, but of course, the chart was wrong. I knew that, but I’d only been taking it into consideration for keeping an interval from the beach, not avoiding stuff ahead of me.

In retrospect going aground would probably have been okay, because, as I’ve mentioned, the seas were fairly calm and the winds blowing offshore. With our big twin screws, we probably could have backed and twisted ourselves into deeper water. But with 40- to 45-knot winds and utter darkness, it was scary thought at the time . .

We went out about a mile to skirt the sandbars and found ourselves bouncing in square 4- to 5-foot seas, which utterly discombobulated the autopilot so I hand steered until were back on our half-mile interval. I let Chef Charles play the video game for a couple hours while I took a nap.

At 4 a.m. I took over again, wearing a sweatshirt against the cold. By the radar, I thought, we were skirting the shore a little too closely, but I had a heck of a time getting it to the correct interval and steering by waypoint at the same time. After a 2-hour nap, I was out of practice.

At 6, Charles took over for the dawn watch, and never thought to wake me for a most marvelous sight. Through the spray and salt-encrusted glass-the boat was covered in salt-he saw people in groups of two or three on the beach with great big kites. The launched the kites off the beach with fishing nets attached, sending them out into the gulf, then drop the whole rig into the water, and drag for fish. Muy Discovery Channel.

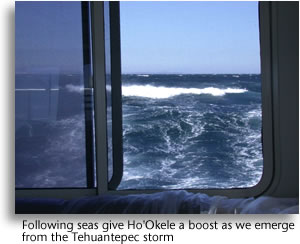

Later as we skirted the petroleum port of Salinas Cruz at the head of the gulf, our course changed to follow the coast and so did the wind. The net result was that wind and seas were now from astern, and Ho’Okele adopted the easy motion that characterizes a Navigator’s down-wave ride. With a comfortable platform and great view of the Sierra Madre to starboard, it was a good time to reflect.

I didn’t regret having wrestled a Tehuantepecker; for one thing, it gave me something to write about other than marinas. But I had to admit, I would not have wanted to do it in my own boat, a 41-foot Morgan Out Island sailboat. Even with its enclosed cockpit, the passage would have been very wet-and noisy with the wind whistling through the rig and halyards slapping. Using flopperstoppers would have been out of the question, so that eliminated any passively stabilized trawler. I couldn’t think of a better boat for the T-Peck Two-Step than a Navigator. Though a well-found trawler with fin stabilizers and fairly shallow draft would also have done just fine..

|