|

In our last dispatch, Ho'Okele had sallied from Golfito, Costa Rica on Christmas Day bound for the infamous Gulf of Papagallo and its gale-force winds. In darkness, our greatest challenge was not the weather, but avoiding gillnets set by Costa Rican fishermen. A lighted buoy marked one end, but in which direction did the nets stretch from there? One smart fisherman saw us coming and steamed toward our bow so that we bore off to port. He flashed a light when we had safely outflanked his nets, though his intent was only clear after the fact. With Ho'Okele in the give-way position, I had been trying to avoid collision. I had tried unsuccessfully to hail him on the radio, calling, "Pescador, pescador, this is USA yacht."

Even in daylight, the nets bedeviled. I found myself in a maze of tiny white floats, which I believed to be two or three of these sets drifted together, each terminating in a black-flagged marker buoy. I guessed my way through this miles-long polypropelene minefield, never totally certain whether I was going around or over the gear. Even in daylight, the nets bedeviled. I found myself in a maze of tiny white floats, which I believed to be two or three of these sets drifted together, each terminating in a black-flagged marker buoy. I guessed my way through this miles-long polypropelene minefield, never totally certain whether I was going around or over the gear.

On the second night out, we noticed strobe lights in our path, which Chef Charles and I assumed were strapped to similar black-flagged marker buoys, and we gave them a wide berth, though without a radar return it was impossible to measure what that meant. All this was happening in less than 300 feet of water, and lent a purpose to our night watches not found in offshore passages. It also underscored a weakness in our preparation as well as the guidebooks upon which we relied for "local" knowledge. Any good guide to waters such as these, it would seem to me, should include a primer on local fishing methods. Such information would provide both strategic (stay in at least 60 fathoms?) and tactical (each net is a half-mile long and laid downwind from the marker buoy?) intelligence to avoid fouling a prop and angering a local fisherman. Though it could only help so much during the net threat, Furuno's C-Map electronic charting had white-knuckle factor from running at night through unfamiliar waters.Relaxed and confident, we maneuvered Ho'Okele around Isla Plata into Potrero Bay at around 1:30 a.m. and dropped the hook. In the morning the wind kicked up into a Papagallo, one of those sudden windstorms said to originate in the Caribbean, and we squeezed into a berth at Marina Flamingo with its protective breakwaters to wait. Marina Flamingo, operated by ex-pat Jim McKenzie, is a rustic sportfish marina strategically located in the northwestern region of Costa Rica. During years of war and anti-American hostility among its northern neighbors, this part of Costa Rica was the first friendly landfall since Mexico, and Flamingo is the only marina. McKenzie's 70-slips and gas docks are cheek and jowl to a modest resort complex that includes two hotels, a half dozen good restaurants and some nightlife. Americans own many of the businesses and make up much of the clientele here. We came, we consumed and in the morning we took on ice and fuel and left. In the middle of a Papagallo.

It's not that I wanted to leave in a storm but I considered three factors:

1. This Papagallo was modest with winds only gusting to 35 knots;

2. No one could tell me when it was going to end, and

3. In five hours of steaming we would surely find relief in the lee of the Nicaraguan shore.

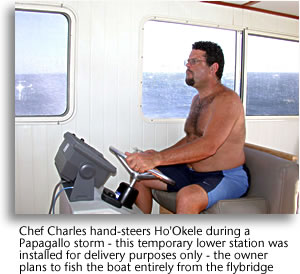

Between Potrero Bay and that blessed lee lay the Gulf of Papagallo and a smaller gulf separated from the former by a sharp headland. Even if we had hugged the Gulf of Papagallo's shore, where seas were calmest, we would still have to round that ugly cape where the fetch from both gulfs would collide in a roiling cauldron of confused seas. We took the direct route. Honestly, the ride wasn't so bad. I adjusted our course so as to avoid beam seas, though at times it was difficult to tell what direction the waves were hitting from. The wind howled and lathered our glass in brine.The autopilot, set for calmer weather, balked, so for the first time in more than 2,000 miles, Chef Charles and I took turns steering by actually putting our hands on the wheel. Between Potrero Bay and that blessed lee lay the Gulf of Papagallo and a smaller gulf separated from the former by a sharp headland. Even if we had hugged the Gulf of Papagallo's shore, where seas were calmest, we would still have to round that ugly cape where the fetch from both gulfs would collide in a roiling cauldron of confused seas. We took the direct route. Honestly, the ride wasn't so bad. I adjusted our course so as to avoid beam seas, though at times it was difficult to tell what direction the waves were hitting from. The wind howled and lathered our glass in brine.The autopilot, set for calmer weather, balked, so for the first time in more than 2,000 miles, Chef Charles and I took turns steering by actually putting our hands on the wheel.

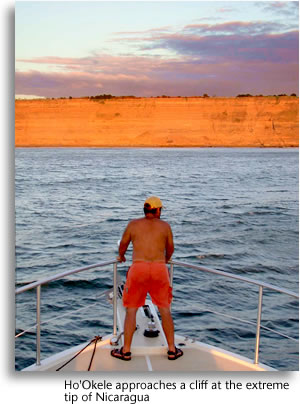

That night we skirted the coast of Nicaragua as the Papagallo faded away. We had decided to spend the New Year's Holiday at a new Marina in El Salvador, a nation shunned by our guidebooks. Things, however, had changed since the El Salvadoran civil war ended 15 years ago, and an enterprising family had started a first-rate facility, which you will surely hear about in the future. Golfito's marina owner had recommended Barillas Marina Club to us, and a delivery skipper along the way had seconded the motion. Our problem was that there would be no night entry into Jiquilisco Bay, which was uncharted and defended by a lively sandbar. Ho'Okele would either have to slow down or stop for the night to effect a daylight arrival. We chose the latter after catching a "football" of a yellow-fin tuna. We hove under a cliff on the northernmost coast of Nicaragua and dropped the hook in 16 feet of water. That night we skirted the coast of Nicaragua as the Papagallo faded away. We had decided to spend the New Year's Holiday at a new Marina in El Salvador, a nation shunned by our guidebooks. Things, however, had changed since the El Salvadoran civil war ended 15 years ago, and an enterprising family had started a first-rate facility, which you will surely hear about in the future. Golfito's marina owner had recommended Barillas Marina Club to us, and a delivery skipper along the way had seconded the motion. Our problem was that there would be no night entry into Jiquilisco Bay, which was uncharted and defended by a lively sandbar. Ho'Okele would either have to slow down or stop for the night to effect a daylight arrival. We chose the latter after catching a "football" of a yellow-fin tuna. We hove under a cliff on the northernmost coast of Nicaragua and dropped the hook in 16 feet of water.

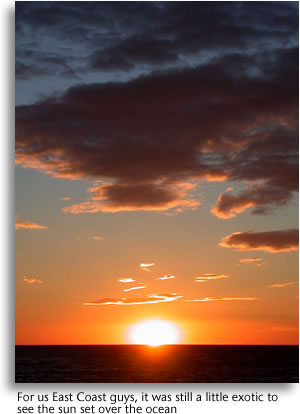

Four volcanoes loomed to our north and east. As the grill glowed, a setting sun blushed orange over the Pacific Ocean, reminding us of why we do things like this. My culinary vocabulary cannot describe the taste of that fish, served as it was with a Wasabe-pineapple sauce, rice on the side. By 2 p.m. the next day we were knocking at the gates Barillas Marina Club. More accurately, we were hailing the club on Channel 16 because the plotter said the waypoint for Jiquilisco Bay (13 07 N, 88 25 W) was an hour away. The white panga was difficult to discern in the whitecaps and 5-foot seas, but finally our guide boat crested a wave and appeared before us, our pilot waving broadly. We followed. Soon two waverunners appeared and circled us, one of which we later learned was manned by Juan Wright, president of the marina company. Ho'Okele's escort would be a royal one. We flanked the breaking bar, and took a broad turn into the bay. We passed a fishing village on a beach lined with pangas. We continued behind our guide into a mangrove channel, and by the time we saw the mooring field we were about 10 miles from that initial waypoint. Four volcanoes loomed to our north and east. As the grill glowed, a setting sun blushed orange over the Pacific Ocean, reminding us of why we do things like this. My culinary vocabulary cannot describe the taste of that fish, served as it was with a Wasabe-pineapple sauce, rice on the side. By 2 p.m. the next day we were knocking at the gates Barillas Marina Club. More accurately, we were hailing the club on Channel 16 because the plotter said the waypoint for Jiquilisco Bay (13 07 N, 88 25 W) was an hour away. The white panga was difficult to discern in the whitecaps and 5-foot seas, but finally our guide boat crested a wave and appeared before us, our pilot waving broadly. We followed. Soon two waverunners appeared and circled us, one of which we later learned was manned by Juan Wright, president of the marina company. Ho'Okele's escort would be a royal one. We flanked the breaking bar, and took a broad turn into the bay. We passed a fishing village on a beach lined with pangas. We continued behind our guide into a mangrove channel, and by the time we saw the mooring field we were about 10 miles from that initial waypoint.

|